The love in my heart has died many times. It has been crushed by the boulder of my pride, preventing me from loving by ensuring that I never saw the needs of another, tending only to my own desires which so filled my vision. My fear has suffocated it, preventing me from reaching out in love to others who most needed my strength and courage, pulling out of me all that is truly alive, stopping the breath of love that fuels each beat of a loving heart.

Over and over, I have missed the mark of divine love, whether because of my wrath, my sloth, my envy, my gluttony, my greed, or my lust. Over and over again, my love has been wounded, scourged on its way to death by my sins which separate me from divine love. Over and over again, my heart has been emptied of love as it was shoveled out by the efforts of pleasure-seeking, the work of my slavery to the ego from which I long to be free.

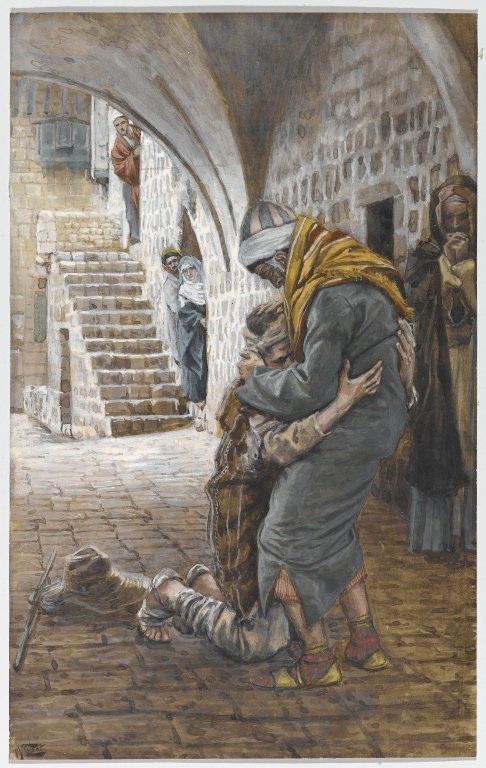

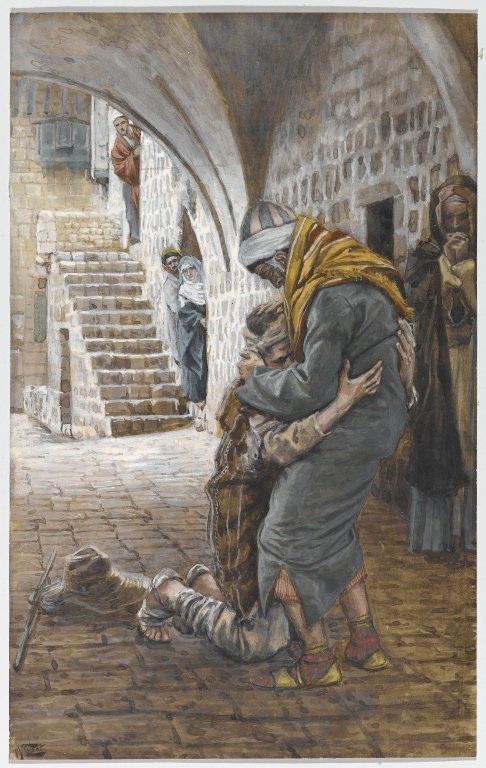

And yet each time my love has died, no matter how wounded or battered I have left it, love has risen again in my heart, called forth from the tomb into the garden of life. While I was trapped in the darkness of my sins, a great light has shown me the path to love. Though I descended to hell on earth where divine love is locked out by my refusal of His invitation, Love opened the door to my hardened heart and stretched out His hand to me, asking me to embrace Him once again and let my heart of stone be softened by love alone.

The love in my heart, like Lazarus, comes forth from the tomb when I heed the Master's voice and do not resign myself to the ultimate death of a life without Love. If I but obey His commands, I can rise to love again, resurrected by the power of Love whose Kingdom is not of this world and therefore is unbound by the laws of this world. My love is resurrected by the one who loved us unto death, descended to Hades and broke its doors in two so that the righteous dead might rise again, those who were asleep awakened to a new life with the resurrected Love.

The resurrection of Christ which we celebrate at Pascha (known as Easter in English) is the resurrection of Love Himself, the glorious return of the builder of the world to the garden of life, and He does not return alone. He invites with Him the children of Adam and Eve who were asleep in Hades, restoring them to the paradise of love for which they were made. The Lamb of God who was slain for our sins returns as the Good Shepherd to lay us down in great pastures, to lead us by the Living Water from which we gain eternal life, our souls restored by the Cup of Love poured out for us.

He loved to death the sting of death by bearing our sins upon the cross, showing us that we too must follow Him in loving to death the sting of death in our lives which is called sin, taking up our cross daily and falling under its weight so that one day we might rise again with Him. Love showed us that the only way to resurrection is through the tomb, that we must love to death all that would keep us from rising again to new life.

He showed us by His life that we must accept His invitation to resurrect the love in our hearts if we would be resurrected in body and mind, that before we can rise with Him we must fully love God with all of our strength and our neighbor as ourselves, keeping the law of Love which fulfills the Law of Moses. He calls us to love to death all that separates us from the Love who is not bound by the laws of this world, to love Him by keeping the Law he gives to us, the Law of Love which frees us from the slavery of sin when we practice it diligently by teaching us to hit the mark of divine love.

He showed us that to way to love sin to death is by a life dedicated to service to the poor and vulnerable, mercy and a call to repentance for the condemned, and love for the enemies who hate us. He showed us that by loving to death all that is not of divine love in our life, we have hope for the resurrection of all those who love Him in the Resurrection of Love.

Let us resurrect the divine love of Love in our hearts each day so that we may share it with others and help them to accept His invitation to leave the life of slavery to sin so as to share in the Resurrection of Christ who is Love, drawn by His hand out of the tomb of death and into the garden of life.

By Surgun100 - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8724640

Note: This icon depicting the resurrection of Christ shows us that as He was resurrected from the grave, so too does he lift us up from the grave, trampling down death by death.

I'm at the end of my wisdom, and here I will remain as its limits grow into the event horizon of love.

Quotation

He who learns must suffer, and, even in our sleep, pain that we cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, and in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom to us by the awful grace of God. - Aeschylus

Monday, March 28, 2016

Sunday, March 27, 2016

Praying with the Gospels: Carrying the Cross

Lord, as I go about my business, journeying to the Holy Land where

Your chosen people dwell, I am told that I must share the burden of

another, one who has been cast out into the darkness outside by their

judgment that it is better that one should be killed than that many of

the people should be slaughtered like fattened calves offered to You.

Please help me by Your grace to ever provide help to You through a

sharing of the burdens carried by Your least brothers and sisters, that

I may not begrudge them the help they require of me in carrying the

cross they have taken up, the cross under which they have fallen at

times as they struggle to walk the via dolorosa walked first by You.

Christ my God, let me remember that as You fell carrying the cross,

so too will I fall carrying my cross and ask another to help me bear

it with me, carrying the cross under which I have fallen by my sins

many times only to stand and walk at Your word again without fear,

trusting that as You rose to glory I may also rise to glory with You.

By Andrea di Bartolo - http://www.phombo.com/miscellaneous/european-paintings-and-sculpture-from-12th-to-mid-19th-centuries/775454/full/popular/ 2010-10-05, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15367980

Note: The man who carried Jesus' cross to the mount of execution was Simon of Cyrene, and this event is one of the Stations of the Cross.

Your chosen people dwell, I am told that I must share the burden of

another, one who has been cast out into the darkness outside by their

judgment that it is better that one should be killed than that many of

the people should be slaughtered like fattened calves offered to You.

Please help me by Your grace to ever provide help to You through a

sharing of the burdens carried by Your least brothers and sisters, that

I may not begrudge them the help they require of me in carrying the

cross they have taken up, the cross under which they have fallen at

times as they struggle to walk the via dolorosa walked first by You.

Christ my God, let me remember that as You fell carrying the cross,

so too will I fall carrying my cross and ask another to help me bear

it with me, carrying the cross under which I have fallen by my sins

many times only to stand and walk at Your word again without fear,

trusting that as You rose to glory I may also rise to glory with You.

By Andrea di Bartolo - http://www.phombo.com/miscellaneous/european-paintings-and-sculpture-from-12th-to-mid-19th-centuries/775454/full/popular/ 2010-10-05, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15367980

Note: The man who carried Jesus' cross to the mount of execution was Simon of Cyrene, and this event is one of the Stations of the Cross.

Friday, March 25, 2016

Love it to Death: The Icons of Love

This past Sunday I was at the Feast of the Triumph of Orthodoxy at the local Orthodox parish. As he often does, the pastor provided a brief explanation of the origins of the feast, which was the end of the power of the Iconoclast heretics and the restoration of icons to the churches by the Regent Theodora. The Iconoclasts had gained their power by the fact that the emperor Leo III had agreed with them and had been willing to use Byzantine imperial power to enforce his views by banning the use of icons.

When an underwater volcano wreaked havoc upon parts of the empire, many people, including (it seems) Leo III, believed that this was a sign of God's wrath, and then inferred that what had caused God's wrath was the use of religious images. Interestingly, common superstition lead to a concern with idolatry, and this then lead to violence as those who believed that the images were idols (iconoclasts) and those who thought them worthy of veneration (iconodules) clashed over the issue. Because the Emperor at the time agreed with the iconoclasts, many icons were destroyed, and this is in large part why there are so few Byzantine icons remaining from the era prior to the first Imperial spasm of iconoclasm.

The priest of the Orthodox parish helpfully explained the reason for our continued veneration of icons despite the prohibition of graven images in the Ten Commandments. He pointed out that until God was incarnate in the form of Jesus Christ, there was no God in the world which could be represented by the use of images. Because God Himself had not showed the Israelites an icon of Himself, God could not be depicted as an icon. That is, until God became incarnate, sending His only begotten Son in human form, God clothed in the image and likeness of God.

We know from Sacred Scripture, specifically Genesis, that from the beginning we have been made in the image of God and bear His likeness. For those of us in the Latin tradition, this is often referred to as imago dei, a concept I've referenced before. For those in the Greek tradition, the term is eikōn, rendered as icon in English. This term is used in the Septuagint in the passage which explains that we are made in the image of God. According to Sacred Scripture, we are all icons of the living God, made by Him in His image and bearing His likeness. God created us as icons, so we know that icons are good, which may be why we keep so many of those we love.

The pictures I have in my apartment of my family, friends, and godchildren are very much images of people I love, icons of those created in God's image just as the Saints are, but no one suspects me of worshiping them. And though my Protestant grandmother's house is so thoroughly lined with pictures as to be reminiscent of the way Orthodox and Catholic churches are covered in images, no one would ever suspect her of worshiping them no matter how often she has filled her house with prayer and worship. And if she were to kiss an image of my grandfather who has passed away and hope in her heart that he could see her and pray for her from Heaven, many would think it a touching testament to her love for him.

They would probably admire my grandmother's devotion, and rightly so. But when the Orthodox or Catholic grandmother shows devotion to an icon by kissing it or touching it, many of the same folks are much more likely to worry than to admire her devotion to the Communion of Saints. And when those who are Orthodox and Catholic cover the house of God with the images of those He loves and those who love Him, painted and sculpted images of the members of the family of Love who have been adopted into the divine household through the Blood of Christ, some are concerned that this is idolatry.

This is, of course, understandable. We humans are prone to worshiping other human beings, the icons of the living God, instead of worshiping God. Many a lover has begun to worship his beloved, placing her on a pedestal in his heart, placing her above even God. And this is indeed iconolatry, a grave sin to be avoided at great cost. We should neither worship one another as icons of the living God nor worship painted or sculpted icons of one another.

We should go no father than dulia for the icons of the living God, venerating them for their godliness but not worshiping them as God. And just as God did not refrain from creating icons in His image, knowing that they would sometimes worship one another, the ancient Church did not refrain from creating icons in His image though it was likely that some would fall to worship them. Neither God nor His Church keep back from His People the good things of the world, though we may do evil with them.

And we who are icons created by the God who is Love are bound to participate in God's love which creates icons; thus it is natural and right for those who participate in God's love to also create icons, images of the living God and images of the icons he has created out of His great Love. We are the icons of Love, and we cannot help but show our love for Him by creating icons of Love and icons of those who He loves.

How can we not create icons of Love when He sent us the very Icon of Love? Christ is indeed both Love and the Icon of Love, God in the form of an icon. Christ Himself tells us in the Gospels that through Him we see the Father (John 4:19). In the Incarnation, God took to Himself an icon and became the true Image of God. Christ is the imago dei who shows us how to be more fully an imago dei; Christ shows us the path we must walk, the via dolorosa which leads those of us who are icons of Love into being united with Love.

Christ is the very Icon of Love, and even He was destroyed on the cross; His death was the destruction of the most holy icon of all, the ultimate iconoclasm. If even Christ, the Icon of Love, is smashed by the iconoclasts of the time who could not imagine a greater blasphemy than a man who was God in the image of God, then is it any surprise that many other icons of Love would be smashed by iconoclasts?

The holy martyrs, like us, are icons of the living God, the images of God crushed in their infirmity; like Christ, they will rise to glory. We are called to follow them, to willingly separate ourselves from anything which might keep us from being beautiful icons of Love, to divest ourselves of all that is not a reflection of the light of divine love. Like the holy martyrs, we are called to love to death all that prevents us, we who are images of God, from being united with the one whose likeness we bear.

As we reflect the light of the Icon of Love, we become more and more the image and likeness of God, icons of ever greater beauty. Just as those who paint icons pray while they paint in order that their icons might become holy icons, so too we are called to pray in order that we might become holy, icons who increasingly resemble the great beauty of their love He who is Love.

In imitating Christ, He who is the Icon of Love, we are gradually transformed into ever more clear and more beautiful icons of Love; by His grace we are granted to be perfect just as our heavenly Father is perfect.

By Anonymous - National Icon Collection (18), British Museum, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7306236

Note: The image is an icon depicting the restoration of icons to the churches under Theodora and Michael III.

When an underwater volcano wreaked havoc upon parts of the empire, many people, including (it seems) Leo III, believed that this was a sign of God's wrath, and then inferred that what had caused God's wrath was the use of religious images. Interestingly, common superstition lead to a concern with idolatry, and this then lead to violence as those who believed that the images were idols (iconoclasts) and those who thought them worthy of veneration (iconodules) clashed over the issue. Because the Emperor at the time agreed with the iconoclasts, many icons were destroyed, and this is in large part why there are so few Byzantine icons remaining from the era prior to the first Imperial spasm of iconoclasm.

The priest of the Orthodox parish helpfully explained the reason for our continued veneration of icons despite the prohibition of graven images in the Ten Commandments. He pointed out that until God was incarnate in the form of Jesus Christ, there was no God in the world which could be represented by the use of images. Because God Himself had not showed the Israelites an icon of Himself, God could not be depicted as an icon. That is, until God became incarnate, sending His only begotten Son in human form, God clothed in the image and likeness of God.

We know from Sacred Scripture, specifically Genesis, that from the beginning we have been made in the image of God and bear His likeness. For those of us in the Latin tradition, this is often referred to as imago dei, a concept I've referenced before. For those in the Greek tradition, the term is eikōn, rendered as icon in English. This term is used in the Septuagint in the passage which explains that we are made in the image of God. According to Sacred Scripture, we are all icons of the living God, made by Him in His image and bearing His likeness. God created us as icons, so we know that icons are good, which may be why we keep so many of those we love.

The pictures I have in my apartment of my family, friends, and godchildren are very much images of people I love, icons of those created in God's image just as the Saints are, but no one suspects me of worshiping them. And though my Protestant grandmother's house is so thoroughly lined with pictures as to be reminiscent of the way Orthodox and Catholic churches are covered in images, no one would ever suspect her of worshiping them no matter how often she has filled her house with prayer and worship. And if she were to kiss an image of my grandfather who has passed away and hope in her heart that he could see her and pray for her from Heaven, many would think it a touching testament to her love for him.

They would probably admire my grandmother's devotion, and rightly so. But when the Orthodox or Catholic grandmother shows devotion to an icon by kissing it or touching it, many of the same folks are much more likely to worry than to admire her devotion to the Communion of Saints. And when those who are Orthodox and Catholic cover the house of God with the images of those He loves and those who love Him, painted and sculpted images of the members of the family of Love who have been adopted into the divine household through the Blood of Christ, some are concerned that this is idolatry.

This is, of course, understandable. We humans are prone to worshiping other human beings, the icons of the living God, instead of worshiping God. Many a lover has begun to worship his beloved, placing her on a pedestal in his heart, placing her above even God. And this is indeed iconolatry, a grave sin to be avoided at great cost. We should neither worship one another as icons of the living God nor worship painted or sculpted icons of one another.

We should go no father than dulia for the icons of the living God, venerating them for their godliness but not worshiping them as God. And just as God did not refrain from creating icons in His image, knowing that they would sometimes worship one another, the ancient Church did not refrain from creating icons in His image though it was likely that some would fall to worship them. Neither God nor His Church keep back from His People the good things of the world, though we may do evil with them.

And we who are icons created by the God who is Love are bound to participate in God's love which creates icons; thus it is natural and right for those who participate in God's love to also create icons, images of the living God and images of the icons he has created out of His great Love. We are the icons of Love, and we cannot help but show our love for Him by creating icons of Love and icons of those who He loves.

How can we not create icons of Love when He sent us the very Icon of Love? Christ is indeed both Love and the Icon of Love, God in the form of an icon. Christ Himself tells us in the Gospels that through Him we see the Father (John 4:19). In the Incarnation, God took to Himself an icon and became the true Image of God. Christ is the imago dei who shows us how to be more fully an imago dei; Christ shows us the path we must walk, the via dolorosa which leads those of us who are icons of Love into being united with Love.

Christ is the very Icon of Love, and even He was destroyed on the cross; His death was the destruction of the most holy icon of all, the ultimate iconoclasm. If even Christ, the Icon of Love, is smashed by the iconoclasts of the time who could not imagine a greater blasphemy than a man who was God in the image of God, then is it any surprise that many other icons of Love would be smashed by iconoclasts?

The holy martyrs, like us, are icons of the living God, the images of God crushed in their infirmity; like Christ, they will rise to glory. We are called to follow them, to willingly separate ourselves from anything which might keep us from being beautiful icons of Love, to divest ourselves of all that is not a reflection of the light of divine love. Like the holy martyrs, we are called to love to death all that prevents us, we who are images of God, from being united with the one whose likeness we bear.

As we reflect the light of the Icon of Love, we become more and more the image and likeness of God, icons of ever greater beauty. Just as those who paint icons pray while they paint in order that their icons might become holy icons, so too we are called to pray in order that we might become holy, icons who increasingly resemble the great beauty of their love He who is Love.

In imitating Christ, He who is the Icon of Love, we are gradually transformed into ever more clear and more beautiful icons of Love; by His grace we are granted to be perfect just as our heavenly Father is perfect.

By Anonymous - National Icon Collection (18), British Museum, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7306236

Note: The image is an icon depicting the restoration of icons to the churches under Theodora and Michael III.

Monday, March 21, 2016

The Liturgy of the Minutes

In the ancient Christian churches, it's often the case that formal prayer is not just prior to meals or during Sunday worship or during meetings with other members of one's church or before bed with one's children. Those are all wonderful times to pray, and we ought to pray at those times. But in the Letter to the Thessalonians, we are advised to pray without ceasing, and this is where the Liturgy of the Hours comes in.

As I've mentioned before, in the liturgy we lift up our hearts in love and are lifted up in the embrace of divine love, and by this love we gradually put to death those parts of us that can not partake of divine love. In the liturgy is loving intimacy with the divine, the greatest form of prayer to the one who loved us unto death. Because we love Him, we want to join with all those who love Him in this greatest form of prayer, the extravagance of our love for God shining forth in the forms and sounds, in the incense and the vestments, in the precious metals for the Precious Body and Precious Blood.

Because the Church desires to express the extravagance of our love for Christ our God without ceasing, She has given us the Liturgy of the Hours, which is composed of Morning Prayer, Daytime Prayer, The Office of Readings, Evening Prayer, and Night Prayer. Like many gifts of the Church, the Liturgy of the Hours is rich in history and tradition spanning from pre-exilic Judaism to the desert hermits and monastics of early Christianity. The monks and hermits built their lives around daily prayers from the Psalms and from the tradition of the early Church, passing those prayers on to all the faithful so that they too might pray from the heart of the Church.

The Church invites us to begin each day with prayer, to continue each day with prayer, to dive each day into Sacred Scripture through the Psalms, to fill each evening with prayer, and to end each day with prayer. This is the unending sacrifice of praise offered first by the exiled Jews in the synagogue and now by the Church to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be.

Even within the small moments of each day, when waiting for our turn in the grocery line, sitting still as a train rumbles down the tracks, or running a trail at sunset, the Church invites us back to the liturgy. No matter how small the number of minutes we have, they can be filled by the meditation on the Gospels that is the Christocentric rosary which keeps our gaze always upon Christ and His good news of salvation. No matter how great the number of minutes we have, they can be an unending unveiling of Jesus as man, Christ, and God through the Apocalyptic rosary.

If we choose it, our lives can be a liturgy of minutes; whether we pray the Liturgy of the Hours, the Dominican rosary, the Chaplet of St. Michael, or the Franciscan Crown rosary, we can pray without ceasing, making each minute a meaningful moment of showing God our love for Him. Each minute is an opportunity for liturgy, an opportunity to cultivate an intimate relationship with the God who loved us unto death, reciprocating His love for us by making a sacrifice of the time He has given to us by filling it with praise.

As I've mentioned before, in the liturgy we lift up our hearts in love and are lifted up in the embrace of divine love, and by this love we gradually put to death those parts of us that can not partake of divine love. In the liturgy is loving intimacy with the divine, the greatest form of prayer to the one who loved us unto death. Because we love Him, we want to join with all those who love Him in this greatest form of prayer, the extravagance of our love for God shining forth in the forms and sounds, in the incense and the vestments, in the precious metals for the Precious Body and Precious Blood.

Because the Church desires to express the extravagance of our love for Christ our God without ceasing, She has given us the Liturgy of the Hours, which is composed of Morning Prayer, Daytime Prayer, The Office of Readings, Evening Prayer, and Night Prayer. Like many gifts of the Church, the Liturgy of the Hours is rich in history and tradition spanning from pre-exilic Judaism to the desert hermits and monastics of early Christianity. The monks and hermits built their lives around daily prayers from the Psalms and from the tradition of the early Church, passing those prayers on to all the faithful so that they too might pray from the heart of the Church.

The Church invites us to begin each day with prayer, to continue each day with prayer, to dive each day into Sacred Scripture through the Psalms, to fill each evening with prayer, and to end each day with prayer. This is the unending sacrifice of praise offered first by the exiled Jews in the synagogue and now by the Church to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be.

Even within the small moments of each day, when waiting for our turn in the grocery line, sitting still as a train rumbles down the tracks, or running a trail at sunset, the Church invites us back to the liturgy. No matter how small the number of minutes we have, they can be filled by the meditation on the Gospels that is the Christocentric rosary which keeps our gaze always upon Christ and His good news of salvation. No matter how great the number of minutes we have, they can be an unending unveiling of Jesus as man, Christ, and God through the Apocalyptic rosary.

If we choose it, our lives can be a liturgy of minutes; whether we pray the Liturgy of the Hours, the Dominican rosary, the Chaplet of St. Michael, or the Franciscan Crown rosary, we can pray without ceasing, making each minute a meaningful moment of showing God our love for Him. Each minute is an opportunity for liturgy, an opportunity to cultivate an intimate relationship with the God who loved us unto death, reciprocating His love for us by making a sacrifice of the time He has given to us by filling it with praise.

Saturday, March 19, 2016

Praying with Gospels: The Eyes of the Blind

Lord, I was born blind to Your physical form in this world,

unable to see You resurrected, Your earthly glory unfurled.

I was born into a world of sin, and I have added to the sins

of the world by my most grievous fault which ever begins

again the process of separating me from Your divine love.

Send me wherever You will, and I will go there to perform

whatever task You set for me; though Your two hands form

clay over my eyes, I trust in Your providence and will walk

confidently to the baptismal pool where others might balk,

and if You but say the word, Your servant shall be healed.

Please help me by Your grace to always choose Your love

over all else so that I may no longer be sin's willing slave,

tearing away all that separates me from Your communion

of love in the eternal heavenly glory of the Beatific vision,

the very imago dei viewed by those who die in Your Love.

By Andrey Mironov - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30520270

Note: This prayer is inspired by the occasion of Jesus' healing of the blind man recounted in the Gospel of John, as well as the Confiteor and another liturgical prayer my fellow Roman Catholics will recognize.

unable to see You resurrected, Your earthly glory unfurled.

I was born into a world of sin, and I have added to the sins

of the world by my most grievous fault which ever begins

again the process of separating me from Your divine love.

Send me wherever You will, and I will go there to perform

whatever task You set for me; though Your two hands form

clay over my eyes, I trust in Your providence and will walk

confidently to the baptismal pool where others might balk,

and if You but say the word, Your servant shall be healed.

Please help me by Your grace to always choose Your love

over all else so that I may no longer be sin's willing slave,

tearing away all that separates me from Your communion

of love in the eternal heavenly glory of the Beatific vision,

the very imago dei viewed by those who die in Your Love.

By Andrey Mironov - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30520270

Note: This prayer is inspired by the occasion of Jesus' healing of the blind man recounted in the Gospel of John, as well as the Confiteor and another liturgical prayer my fellow Roman Catholics will recognize.

Fair Questions: How did the Buddha become enlightened?

As with a long list of many other things (i.e. the Buddha's teaching on wifely submission, the Buddha's views on the economic policies of monarchs, and his placement of morality before mindfulness) I was somewhat surprised by the narrative of the Buddha's journey to enlightenment as recorded in the Pāli canon. I had been under the impression that it was a fairly rapid process that spanned less than a year, that he sat under a tree for a short while and just waited for realization to hit him over the head, perhaps in the form of an apple.

But as I was reading the Ariyapariya Sutta, I discovered that it wasn't at all that simple. Like the Buddha's narrative about his final birth, the Buddha's narrative about his final life in the cosmos of suffering has some unexpected elements.

The first surprise for me was the length of time it seemed to have taken. I realized while reading that the Buddha's journey had begun long before he sat under that fateful tree and attempted to starve himself to death. As with most journeys we take in life, the Buddha's journey began in his own mind; he was searching for something that he was not finding in his current life, a life of plenty that most people would want to have.

The Buddha here explains that what most of us search for in life is not the noble search, that what we search for is not anything that will lead to any permanent state of happiness, that these things and these relationships and these powers over others will not do anything to accomplish the cessation of suffering, but instead keep us trapped in the cycle of death and rebirth.

By stark contrast, the Buddha advises us that the noble search is exclusively for that which is not impermanent, for that which is perfectly pure, for that which is free of suffering and death and the ravages of time. And lest we think that the Buddha does not understand our plight, he assures us that he too has undertaken the ignoble search.

The ignoble search failed to yield the permanent state of happiness so many of us seek, a state free from sorrow and suffering and death. And so the Buddha chose, after some time, to abandon all that kept him on the path of the ignoble search; he then took up the noble search and began with the radical self-denial of living without a home and without his family.

But like most of us, he did not choose to live in complete solitude, but rather sought others who were also on the noble search. He sought out those who, like him, we engaged in a pursuit of freedom from the powers of suffering and death.

The Buddha's consistent emphasis on learning by direct experience is on display here, as it is in many of his discourses. It's quite possible that Ālāra Kālāma was the first teacher to make clear to him the necessity of realization by direct experience, but it's also possible that the Buddha was already committed to finding out the Dhamma by direct experience for himself. Either way, we can tell that he was not satisfied with mere rote knowledge.

The Buddha is also not satisfied with the teaching about the base of nothingness, which according to the translator's footnotes is referring to, "...the plane of existence called the base of nothingness, the objective counterpart of the seventh meditative attainment. Here the lifespan is said to be 60,000 eons, but when that has elapsed one must pass away and return to a lower world. Thus one who attains this is still not free from birth and death."

Though sincerely desiring to learn and respectful of his teacher, the yogic meditation adept who had recognized his progress on the journey of the spiritual life and offered him a place as a fellow adept, the Buddha chose to continue the noble search elsewhere. Specifically, he sought the guidance of Uddaka Rāmaputta, another master of meditation.

The Buddha is once again taught another doctrine, and hoping that it will lead to the end of suffering and death amidst the cycle of death and rebirth, he sincerely attempts to live it out.

Once again he matches the teacher, but the teacher is the son of Rāma, the 7th avatar of Vishnu. Though he is now learning divine wisdom, will it be enough to reach the enlightenment he seeks?

Here we find out that the Buddha is also not satisfied with the teaching about the base of neither-perception-nor-nonperception, and according to the translator's footnotes, "This is the fourth and highest attainment. It should be noted that Uddaka Rāmaputta is Rāma's son, not Rāma himself. ... The attainment of this base leads to rebirth in the base of neither-perception-nor-nonperception, the highest plane of rebirth in the saṃsāra. The lifespan there is said to be 84,000 eons, but being conditioned and impermanent, it is still ultimately unsatisfactory."

Not being satisfied with his becoming a skilled meditator of great talent, character, and understanding of the Dhamma under the teachings of the existing religious figures, respected and saintly though they may have been, the Buddha continued his noble search.

The end of the Buddha's noble search begins in a grove of trees next to a flowing river where he chose to remain until he reached enlightenment, practicing radical self-denial until he found it. His last birth (and a glorious birth it was according to his disciple's recitation) had now culminated in enlightenment and his last death.

Though we tend to focus on his last birth and death, the Buddha consistently claimed that after his enlightenment he remembered each of his past lives in detail, including his name and where he was born, and that there were a great multitude of such lives. The Buddha presents us with a noble search that takes many lives to complete, many deaths and rebirths, and many sorrows and sufferings during those lives.

Enlightenment is not something the Buddha reached in a few days sitting under a tree practicing asceticism and meditation one time, but rather something he grew into over many lifetimes. And even in his final lifetime, he put in a great deal of consistent effort into practicing and learning from others to reach enlightenment, sacrificing all that he had along the way.

In the end, enlightenment is attained only with great difficulty, and though the Buddha may have shown us the path to liberation, we have a long way to go on the journey to reach our destination on the other shore where the Buddha stands, the Perfectly Enlightened One who burned himself up to be a shining lighthouse so that we can cross safely.

By myself - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=805982

Note: For those who are interested, you can find more information about the anthology I'm using on my Sources page.

But as I was reading the Ariyapariya Sutta, I discovered that it wasn't at all that simple. Like the Buddha's narrative about his final birth, the Buddha's narrative about his final life in the cosmos of suffering has some unexpected elements.

The first surprise for me was the length of time it seemed to have taken. I realized while reading that the Buddha's journey had begun long before he sat under that fateful tree and attempted to starve himself to death. As with most journeys we take in life, the Buddha's journey began in his own mind; he was searching for something that he was not finding in his current life, a life of plenty that most people would want to have.

"Monks, there are these two kinds of search: the noble search and the ignoble search. And what is the ignoble search? Here someone being himself subject to birth seeks what is also subject to birth; being himself subject to aging, he seeks what is also subject to aging; being himself subject to sickness; being himself subject to death, he seeks what is also subject to death; being himself subject to sorrow, he seeks what is also subject to sorrow; being himself subject to defilement, he seeks what is also subject to defilement.

And what may be said to be subject to birth, aging, sickness, and death; to sorrow and defilement? Wife and children, mean and women slaves, goats and sheep, fowl and pigs, elephants, cattle, horses, and mares, gold and silver: these acquisitions are subject to birth, aging, sickness, and death; to sorrow and defilement; and one who is tied to these things, infatuated with them, and utterly absorbed in them, being himself subject to birth...to sorrow and defilement, seeks what is also subject to birth...to sorrow and defilement."

The Buddha here explains that what most of us search for in life is not the noble search, that what we search for is not anything that will lead to any permanent state of happiness, that these things and these relationships and these powers over others will not do anything to accomplish the cessation of suffering, but instead keep us trapped in the cycle of death and rebirth.

"And what is the noble search? Here someone being himself subject to birth, having understood the danger in what is subject to birth, seeks the unborn supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna; being himself subject to aging, having understood the danger in what is subject to aging, he seeks the unaging supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna; being himself subject to sickness, having understood the danger in what is subject to sickness, he seeks the unailing supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna; being himself subject to dying, having understood the danger in what is subject to dying, he seeks the deathless supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna; being himself subject to sorrow, having understood the danger in what is subject to sorrow, he seeks the sorrowless supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna; being himself subject to defilement, having understood the danger in what is subject to defilement, he seeks the undefiled supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna. This is the noble search."

By stark contrast, the Buddha advises us that the noble search is exclusively for that which is not impermanent, for that which is perfectly pure, for that which is free of suffering and death and the ravages of time. And lest we think that the Buddha does not understand our plight, he assures us that he too has undertaken the ignoble search.

"Monks, before my enlightenment, when I was still only an unenlightened bodhisatta, I too, being myself subject to birth, sought also what is subject to birth; being myself subject to aging, sickness, death, sorrow, and defilement, I sought what was also subject to aging, sickness, death, sorrow, and defilement. Then I considered thus: 'Why, being myself subject to birth, do I seek what is also subject to birth? Why, being myself subject to aging, sickness, death, sorrow, and defilement, do I seek what is also subject to aging, sickness, death, sorrow, and defilement? Suppose that, being myself subject to birth, having understood the danger in what is subject to birth, I seek the unborn supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna. Suppose that, being myself subject to aging, sickness, death, sorrow, and defilement, I seek the unaging, unailing, deathless, sorrowless, and undefiled supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna.'

Later, while still young, a black-haired young man endowed with the blessing of youth, in the prime of life, though my mother and father wished otherwise and wept with tearful faces, I shaved off my hair and beard, put on the ochre robe, and went forth from the home into a life of homelessness."

The ignoble search failed to yield the permanent state of happiness so many of us seek, a state free from sorrow and suffering and death. And so the Buddha chose, after some time, to abandon all that kept him on the path of the ignoble search; he then took up the noble search and began with the radical self-denial of living without a home and without his family.

But like most of us, he did not choose to live in complete solitude, but rather sought others who were also on the noble search. He sought out those who, like him, we engaged in a pursuit of freedom from the powers of suffering and death.

"Having gone forth, monks, in search of what is wholesome, seeking the supreme state of sublime peace, I went to Ālāra Kālāma and said to him, 'Friend Kālāma, I want to lead the spiritual life in this Dhamma and Discipline.' Ālāra Kālāma replied: 'The venerable one may stay here. This Dhamma is such that a wise man can soon enter upon and dwell in it, realizing for himself through direct knowledge his own teacher's doctrine.' I soon quickly learned that Dhamma. As far as mere lip-reciting and rehearsal of his teaching went, I could speak with knowledge and assurance, and I claimed, 'I know and see'--and there were others who did likewise.

I considered: 'It is not through mere faith alone that Ālāra Kālāma declares: "By realizing it for myself with direct knowledge, I enter upon and dwell in this Dhamma." Certainly Ālāra Kālāma dwells knowing and seeing this Dhamma.' Then I went to Ālāra Kālāma and asked him: 'Friend Kālāma, in what way do you declare that by realizing it for yourself with direct knowledge you enter upon and dwell in this Dhamma?' In reply he declared the base of nothingness."

The Buddha's consistent emphasis on learning by direct experience is on display here, as it is in many of his discourses. It's quite possible that Ālāra Kālāma was the first teacher to make clear to him the necessity of realization by direct experience, but it's also possible that the Buddha was already committed to finding out the Dhamma by direct experience for himself. Either way, we can tell that he was not satisfied with mere rote knowledge.

"I considered: 'Not only Ālāra Kālāma has faith, energy, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom. Suppose I endeavor to realize the Dhamma that Ālāra Kālāma declares he enters upon and dwells in by realizing it for himself by direct knowledge?'

I soon quickly entered upon and dwelled in that Dhamma by realizing it for myself with direct knowledge. Then I went to Ālāra Kālāma and asked him: 'Friend Kālāma, is it in this way that you declare that you enter upon and dwell in this Dhamma by realizing it for yourself with direct knowledge?'--'That is the way, friend.'--'It is in this way, friend, that I also enter upon and dwell in this Dhamma by realizing it for myself with direct knowledge.'--'It is a gain for us, friend, it is a great gain for us that we have such a venerable one for our fellow monk. So the Dhamma that I declare I enter upon and dwell in by realizing it for myself with direct knowledge is the Dhamma that you enter upon and dwell in by realizing for yourself with direct knowledge. ... So you know the Dhamma that I know and I know the Dhamma that you know. As I am, so are you; as you are, so am I. Come, friend, let us now lead this community together.'

Thus Ālāra Kālāma, my teacher, placed me, his pupil, on an equal footing with himself and awarded me the highest honor. But it occurred to me: 'This Dhamma does not lead to disenchantment, to dispassion, to cessation, to peace, to direct knowledge, to enlightenment, to Nibbāna, but only to rebirth in the base of nothingness.' Not being satisfied with that Dhamma, disappointed with it, I left."

The Buddha is also not satisfied with the teaching about the base of nothingness, which according to the translator's footnotes is referring to, "...the plane of existence called the base of nothingness, the objective counterpart of the seventh meditative attainment. Here the lifespan is said to be 60,000 eons, but when that has elapsed one must pass away and return to a lower world. Thus one who attains this is still not free from birth and death."

Though sincerely desiring to learn and respectful of his teacher, the yogic meditation adept who had recognized his progress on the journey of the spiritual life and offered him a place as a fellow adept, the Buddha chose to continue the noble search elsewhere. Specifically, he sought the guidance of Uddaka Rāmaputta, another master of meditation.

"Still in search, monks, of what is wholesome, seeking the supreme state of sublime peace, I went to Uddaka Rāmaputta and said to him: 'Friend, I want to lead the spiritual life in this Dhamma and Discipline.' Uddaka Rāmaputta replied: 'The venerable one may stay here. This Dhamma is such that a wise man can soon enter upon and dwell in it, realizing for himself through direct knowledge his own teacher's doctrine.' I soon quickly learned that Dhamma. As far as mere lip-reciting and rehearsal of his teaching went, I could speak with knowledge and assurance, and I claimed, 'I know and see'--and there were others who did likewise.

I considered: 'It was not through mere faith alone that Rāma declared: "By realizing it for myself with direct knowledge, I enter upon and dwell in this Dhamma." Certainly Rāma dwelled knowing and seeing this Dhamma.' Then I went to Uddaka Rāmaputta and asked him: 'Friend, in what way did Rāma declare that by realizing it for himself with direct knowledge he entered upon and dwelled in this Dhamma?' In reply Uddaka Rāmaputta declared the base of neither-perception-nor-nonperception."

The Buddha is once again taught another doctrine, and hoping that it will lead to the end of suffering and death amidst the cycle of death and rebirth, he sincerely attempts to live it out.

Once again he matches the teacher, but the teacher is the son of Rāma, the 7th avatar of Vishnu. Though he is now learning divine wisdom, will it be enough to reach the enlightenment he seeks?

I considered: 'Not only Rāma has faith, energy, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom. I too have faith, energy, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom. Suppose I endeavor to realize the Dhamma that Rāma declared he entered upon and dwelled in by realizing it for himself by direct knowledge.'

I soon quickly entered upon and dwelled in that Dhamma by realizing it for myself with direct knowledge. Then I went to Uddaka Rāmaputta and asked him: 'Friend, was it in this way that Rāma declared he entered upon and dwelled in by realizing it for himself by direct knowledge?'--'That is the way, friend.'--'It is in this way, friend, that I also enter upon and dwell in this Dhamma by realizing it for myself with direct knowledge.'--'It is a gain for us, friend, it is a great gain for us that we have such a venerable one for our fellow monk. So the Dhamma that Rāma declared he entered upon and dwelled in by realizing it for himself with direct knowledge is the Dhamma that you enter upon and dwell in by realizing for yourself with direct knowledge. ... So you know the Dhamma that Rāma knew and Rāma knew the Dhamma that you know. As Rāma was, so are you; as you are, so was Rāma. Come, friend, now lead this community.'

Thus Uddaka Rāmaputta, my fellow monk, placed me in the position of a teacher and accorded me the highest honor. But it occurred to me: 'This Dhamma does not lead to disenchantment, to dispassion, to cessation, to peace, to direct knowledge, to enlightenment, to Nibbāna, but only to rebirth in the base of neither-perception-nor-nonperception.' Not being satisfied with that Dhamma, disappointed with it, I left.

Here we find out that the Buddha is also not satisfied with the teaching about the base of neither-perception-nor-nonperception, and according to the translator's footnotes, "This is the fourth and highest attainment. It should be noted that Uddaka Rāmaputta is Rāma's son, not Rāma himself. ... The attainment of this base leads to rebirth in the base of neither-perception-nor-nonperception, the highest plane of rebirth in the saṃsāra. The lifespan there is said to be 84,000 eons, but being conditioned and impermanent, it is still ultimately unsatisfactory."

Not being satisfied with his becoming a skilled meditator of great talent, character, and understanding of the Dhamma under the teachings of the existing religious figures, respected and saintly though they may have been, the Buddha continued his noble search.

"Still in search, monks, of what is wholesome, seeking the supreme state of sublime peace, I wandered by stages through the Magadhan country until eventually I arrived at Uruvelā near Senānigama. There I saw an agreeable piece of ground, a delightful grove with a clear-flowing river with pleasant, smooth banks and nearby a village for alms resort. I considered: 'This is an agreeable piece of ground, a delightful grove with a clear-flowing river with pleasant, smooth banks and nearby a village for alms resort. This will serve for the striving of a clansman intent on striving.' And I sat down there thinking: 'This will server for striving.'

Then, monks, being myself subject to birth, having understood the danger in what is subject to birth, seeking the unborn supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna, I attained the unborn supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna; being myself subject to aging, having understood the danger in what is subject to aging, seeking the unaging supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna, I attained the unaging supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna; being myself subject to sickness, having understood the danger in what is subject to sickness, seeking the unailing supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna, I attained the unailing supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna; being myself subject to death, having understood the danger in what is subject to death, seeking the deathless supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna, I attained the deathless supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna; being myself subject to sorrow, having understood the danger in what is subject to sorrow, seeking the sorrowless supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna, I attained the sorrowless supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna; being myself subject to defilement, having understood the danger in what is subject to defilement, seeking the undefiled supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna, I attained the undefiled supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna. The knowledge and vision arose in me: 'My liberation is unshakable. This is my last birth. Now there is no more renewed existence.'"

The end of the Buddha's noble search begins in a grove of trees next to a flowing river where he chose to remain until he reached enlightenment, practicing radical self-denial until he found it. His last birth (and a glorious birth it was according to his disciple's recitation) had now culminated in enlightenment and his last death.

Though we tend to focus on his last birth and death, the Buddha consistently claimed that after his enlightenment he remembered each of his past lives in detail, including his name and where he was born, and that there were a great multitude of such lives. The Buddha presents us with a noble search that takes many lives to complete, many deaths and rebirths, and many sorrows and sufferings during those lives.

Enlightenment is not something the Buddha reached in a few days sitting under a tree practicing asceticism and meditation one time, but rather something he grew into over many lifetimes. And even in his final lifetime, he put in a great deal of consistent effort into practicing and learning from others to reach enlightenment, sacrificing all that he had along the way.

In the end, enlightenment is attained only with great difficulty, and though the Buddha may have shown us the path to liberation, we have a long way to go on the journey to reach our destination on the other shore where the Buddha stands, the Perfectly Enlightened One who burned himself up to be a shining lighthouse so that we can cross safely.

By myself - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=805982

Note: For those who are interested, you can find more information about the anthology I'm using on my Sources page.

Wednesday, March 16, 2016

Fair Questions: What is the role of the Sangha in Buddhism?

One of the things that initially surprised me when I began studying Buddhism more seriously is that the Buddha put morality before mindfulness. Another was that he had an infancy narrative in the Pāli canon, which by the way is fascinating and well worth reading. Yet another surprise was the Buddha's teachings on the duties of women in the household. But these were certainly not the only surprises I encountered when reading the Pāli canon.

But before I get to the source of my surprise, what is the Pāli canon? It's the oldest extant collection of the Buddha's teachings, transmitted by oral tradition by the monks who were his disciples to later generations, eventually recorded in written form. As is the case with many religious traditions, the texts used by the adherents of Buddhism were not written until later and were written based on the oral tradition of the early Buddhist community.

The early Buddhist community was probably not a unified whole in which every member of the Sangha agreed on every point with every other member of the Sangha, but the first documented splitting of the community into different schools occurred between the time of the second Buddhist council and the third Buddhist council. The Pāli canon was probably the work of this early Buddhist community in much the same way that the New Testament writings were the work of the early Christian community (though the Pāli canon is older than any of the the New Testament canons by several hundred years).

When I refer to the Sangha above, I mean the assembly of Buddhist monks and nuns, though there are understandings of the Sangha which are broader in scope. It was these monks and nuns who preserved the Buddha's teachings, a process we might think of as dharma transmission, the passing on of the truths the Buddha revealed to us about morality, the cosmic order, and transcendence. Without the Sangha, we would not have any writings to refer to when we sought refuge in the Buddha and his teachings.

And even more importantly, without the Sangha there is no lived experience of Buddhism to be handed on to those who want to become Buddhists. As Joanna Piacenza has pointed out, many people who are interested in Buddhism in the West don't have any contact with this lived experience of Buddhism and simply engage in a reductive sort of mindfulness meditation without the benefit of the Sangha's ability to transmit to them the full experience of Buddhism.

This leads them to be what she calls "buddhist Meditators" because they meditate regularly but have no authentic connection to Buddhism proper. As someone who used to be a buddhist Meditator, I can attest that her description of this phenomenon is quite accurate. Fortunately, I was able to move past that point and study Buddhism more deeply. This was largely thanks to the work of the Sangha, and I am grateful for their help.

The Buddha himself does not mince words when describing the importance of the Sangha, but let's begin with the words of his student who learned a valuable lesson and was grateful for it:

Kālāmas, who is learning from the Buddha how to avoid unreliable means of gaining knowledge, presents us with a pretty standard line about going to the Buddha for refuge, because for many the Buddha's teachings are a place where we are free of the dangers of the false views which are ubiquitous in the world. He goes to the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha for refuge from these false views. This is a set of three that I've seen many times in the Pāli canon, reminiscent of the triple munera of Christianity.

The beginning is the Buddha himself, whose friendship is invaluable. The teaching of the Buddha is the timeless Dhamma, which leads to our liberation if we follow it diligently. The Sangha is the preserver and protector of the Dhamma, ensuring that the path of liberation is available to all who seek it. The common denominator here is the Dhamma which liberates; the Buddha is the expounder of the Dhamma and the Sangha safeguards the Dhamma from false views which might overtake it.

This is why the Buddha warns Ānanda, a venerable disciple of the Buddha who features in the discourses of the Pāli canon with some regularity, against anything which damages the integrity of the Sangha.

The Buddha repeats this same point six times with regard to six different types of destructive behavior to the Sangha, the community of the Buddha's disciples, which causes such grave harm to and unhappiness for many people and devas. The Buddha takes pains to point out over and over that there are very serious consequences for both individuals and the world if the Sangha is allowed to disintegrate.

Because the Buddha understands the importance of the continuation of the Sangha, he gives them instructions for ensuring that the community of those who follow the Buddha can thrive:

The Buddha understood that human beings are notoriously prone to allowing themselves to lapse in their routine practices (such as an ascetic lifestyle marked by simple lodgings and almsrounds) which support them on the path to liberation, which leads to a lapse in right conduct (such as communal harmony, respect for those who have gone before, and mindfulness of the body), which then leads to allowing themselves to wander from the path entirely by authorizing behaviors the Buddha prohibited for their good, knowing that if they allowed themselves to engage in those behaviors that cause craving to arise and lead them to yet another rebirth and death in the cosmos of suffering.

After all, the duty of the Sangha is to preserve and protect the Dhamma so that the path to liberation might be available to all beings. This is an extremely important duty; the Sangha acts as a bulwark against the seemingly inevitable onslaught of the endless cycle of death and rebirth. The Sangha must remain faithful to the Dhamma the Buddha has expounded, a brake on the all too human tendency to water down the difficult truths about the effort and discipline required to walk the path to liberation and reach its end.

So how highly does the Buddha place the importance of the Sangha?

In the Buddha's peerless vision, the most important thing he sees is walking the path to liberation by abstaining from immoral behavior, by developing a capacity for boundless loving-kindness, and by cultivating the liberating insight into the impermanence of all things which so indelibly marks the Dhamma as the Buddha expounded it. The second most important thing he lists is the feeding of the monks of the Sangha and building a monastery for them.

This is, of course, not because the Buddha wanted to enrich himself or his followers with fine foods and luxurious living. His ascetic practices, to which he instructed his monks to hold firm, thoroughly reject the excesses of the acquisition of personal wealth and ease. But the community does have a treasury of the greatest wealth to honor with all the honors which can be given in this world, and this wealth is the Dhamma which they are bound to preserve and protect so that all can find refuge in the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha.

The Buddha teaches us that aside from walking the path to liberation for yourself, the best thing one can do is to support the Sangha in its mission to preserve and protect the Dhamma, ensuring that all beings will continue to be able to find the path to the final enlightenment which the Buddha explained so eloquently. By upholding the Sangha which holds fast to the Dhamma, we pass on to those who come after us a compass which points us unerringly in the right direction on the path to liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth.

The ornate temples and meditation rooms in the monasteries, standing in stark contrast to the simple garb, self-denial, and poverty of the monks, point the seekers after liberation towards the path the Buddha showed us. They show us that the path to liberation is worth every worldly honor, that its cost is like that of building the finest temples, and that those who walk the path must give up the pursuit of wealth and pleasure to reach its end.

In the end, the Sangha is the repository of the Dhamma of the Buddha which he left in the world for us; the Sangha is the Buddha's boat, the ship of the Sakyan son in which we can take refuge as we cross to the other shore surely by following always the light of the Buddha himself, he who is the lighthouse.

By Unknown - http://www2.odl.ox.ac.uk/gsdl/cgi-bin/library?e=d-000-00---0orient01--00-0-0-0prompt-10---4------0-1l--1-en-50---20-about---00001-001-1-1isoZz-8859Zz-1-0&a=d&cl=CL1&d=orient001-aaf.14, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41190754

Note: For those who are interested, you can find more information about the anthology I'm using on my Sources page.

But before I get to the source of my surprise, what is the Pāli canon? It's the oldest extant collection of the Buddha's teachings, transmitted by oral tradition by the monks who were his disciples to later generations, eventually recorded in written form. As is the case with many religious traditions, the texts used by the adherents of Buddhism were not written until later and were written based on the oral tradition of the early Buddhist community.

The early Buddhist community was probably not a unified whole in which every member of the Sangha agreed on every point with every other member of the Sangha, but the first documented splitting of the community into different schools occurred between the time of the second Buddhist council and the third Buddhist council. The Pāli canon was probably the work of this early Buddhist community in much the same way that the New Testament writings were the work of the early Christian community (though the Pāli canon is older than any of the the New Testament canons by several hundred years).

When I refer to the Sangha above, I mean the assembly of Buddhist monks and nuns, though there are understandings of the Sangha which are broader in scope. It was these monks and nuns who preserved the Buddha's teachings, a process we might think of as dharma transmission, the passing on of the truths the Buddha revealed to us about morality, the cosmic order, and transcendence. Without the Sangha, we would not have any writings to refer to when we sought refuge in the Buddha and his teachings.

And even more importantly, without the Sangha there is no lived experience of Buddhism to be handed on to those who want to become Buddhists. As Joanna Piacenza has pointed out, many people who are interested in Buddhism in the West don't have any contact with this lived experience of Buddhism and simply engage in a reductive sort of mindfulness meditation without the benefit of the Sangha's ability to transmit to them the full experience of Buddhism.

This leads them to be what she calls "buddhist Meditators" because they meditate regularly but have no authentic connection to Buddhism proper. As someone who used to be a buddhist Meditator, I can attest that her description of this phenomenon is quite accurate. Fortunately, I was able to move past that point and study Buddhism more deeply. This was largely thanks to the work of the Sangha, and I am grateful for their help.

The Buddha himself does not mince words when describing the importance of the Sangha, but let's begin with the words of his student who learned a valuable lesson and was grateful for it:

"Magnificent, venerable sir! Magnificent, venerable sir! The Blessed One has made the Dhamma clear in many ways, as if he were turning upright what had been overthrown, revealing what was hidden, showing the way to one who was lost, or holding up a lamp in the darkness so those with good eyesight can see forms. We now go for refuge to the Blessed One, to the Dhamma, and to the Sangha of monks. Let the Blessed One accept us as lay followers who have gone for refuge from today until life's end."

Kālāmas, who is learning from the Buddha how to avoid unreliable means of gaining knowledge, presents us with a pretty standard line about going to the Buddha for refuge, because for many the Buddha's teachings are a place where we are free of the dangers of the false views which are ubiquitous in the world. He goes to the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha for refuge from these false views. This is a set of three that I've seen many times in the Pāli canon, reminiscent of the triple munera of Christianity.

The beginning is the Buddha himself, whose friendship is invaluable. The teaching of the Buddha is the timeless Dhamma, which leads to our liberation if we follow it diligently. The Sangha is the preserver and protector of the Dhamma, ensuring that the path of liberation is available to all who seek it. The common denominator here is the Dhamma which liberates; the Buddha is the expounder of the Dhamma and the Sangha safeguards the Dhamma from false views which might overtake it.

This is why the Buddha warns Ānanda, a venerable disciple of the Buddha who features in the discourses of the Pāli canon with some regularity, against anything which damages the integrity of the Sangha.

"There are, Ānanda, these six roots of disputes. What six? Here, Ānanda, a monk is angry and resentful. Such a monk dwells without deference toward the Teacher, the Dhamma, and the Sangha, and he does not fulfill the training. A monk who dwells without deference toward the Teacher, the Dhamma, and the Sangha, and who does not fulfill the training, creates a dispute in the Sangha, which would be for the harm and unhappiness of many, for the loss, harm, and suffering of devas and humans."

The Buddha repeats this same point six times with regard to six different types of destructive behavior to the Sangha, the community of the Buddha's disciples, which causes such grave harm to and unhappiness for many people and devas. The Buddha takes pains to point out over and over that there are very serious consequences for both individuals and the world if the Sangha is allowed to disintegrate.

Because the Buddha understands the importance of the continuation of the Sangha, he gives them instructions for ensuring that the community of those who follow the Buddha can thrive:

Soon after Vassakāra had gone, the Blessed One said: "Ānanda, go to whatever monks there are living around Rājagaha, and summon them to the assembly hall."

"Yes, venerable sir," said Ānanda, and he did so. Then he came to the Blessed One, saluted him, stood to one side, and said: "Venerable sir, the Sangha of monks is assembled. Now is the the time for the Blessed One to do as he sees fit." The the Blessed One rose from his seat, went to the assembly hall, sat down on the prepared seat, and said: "Monks, I will teach you seven things that are conducive to welfare. Listen, pay careful attention, and I will speak."

"Yes, venerable sir," said the monks, and the Blessed One said: "As long as the monks hold regular and frequent assemblies, they may be expected to prosper and not decline. As long as they meet in harmony, break up in harmony, and carry on their business in harmony, they may be expected to prosper and not decline. As long as they do not authorize what has not been authorized already, and do not abolish what has been authorized, but proceed according to what has been authorized by the rules of training...; as long as they honor, respect, revere, and salute the elders of long standing who are long ordained, fathers and leaders of the order...; as long as they do not fall prey to the craving that arises in them and leads to rebirth...; as long as they are devoted to forest-lodgings...; as long as they preserve their mindfulness regarding the body, so that in future the good among their companions will come to them, and those who have already come will feel at ease with them...; as long as the monks hold to these seven things and are seen to do so, they may be expected to prosper and not decline."

The Buddha understood that human beings are notoriously prone to allowing themselves to lapse in their routine practices (such as an ascetic lifestyle marked by simple lodgings and almsrounds) which support them on the path to liberation, which leads to a lapse in right conduct (such as communal harmony, respect for those who have gone before, and mindfulness of the body), which then leads to allowing themselves to wander from the path entirely by authorizing behaviors the Buddha prohibited for their good, knowing that if they allowed themselves to engage in those behaviors that cause craving to arise and lead them to yet another rebirth and death in the cosmos of suffering.

After all, the duty of the Sangha is to preserve and protect the Dhamma so that the path to liberation might be available to all beings. This is an extremely important duty; the Sangha acts as a bulwark against the seemingly inevitable onslaught of the endless cycle of death and rebirth. The Sangha must remain faithful to the Dhamma the Buddha has expounded, a brake on the all too human tendency to water down the difficult truths about the effort and discipline required to walk the path to liberation and reach its end.

So how highly does the Buddha place the importance of the Sangha?

The Buddha said to Anathapindika: "In the past, householder, there was a Brahmin named Velama. He gave such a great alms offering as this: 84,000 bowls of gold filled with silver; 84,000 bowls of silver filled with gold; 84,000 bronze bowls filled with bullion; 84,000 elephants, chariots, milch cows, maidens, and couches, many millions of fine cloths, and indescribable amounts of food, drink, ointment, and bedding. As great as was the alms offering that Velama gave, it would be even more fruitful if one were to feed even a single person possessed of right view. ...it would be even more fruitful if one would feed the Sangha of monks headed by the Buddha and build a monastery for the sake of the Sangha of the four quarters...it would be even more fruitful if, with a trusting mind, one would go for refuge to the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha, and would undertake the five precepts: abstaining from the destruction of life, from taking what is not given, from sexual misconduct, from false speech, and from the use of intoxicants. As great as all this might be, it would be even more fruitful if one would develop a mind of loving-kindness even for the time it takes to pull a cow's udder. And as great as all this might be, it would be even more fruitful still if one would develop the perception of impermanence just for the time it takes to snap one's fingers."

In the Buddha's peerless vision, the most important thing he sees is walking the path to liberation by abstaining from immoral behavior, by developing a capacity for boundless loving-kindness, and by cultivating the liberating insight into the impermanence of all things which so indelibly marks the Dhamma as the Buddha expounded it. The second most important thing he lists is the feeding of the monks of the Sangha and building a monastery for them.

This is, of course, not because the Buddha wanted to enrich himself or his followers with fine foods and luxurious living. His ascetic practices, to which he instructed his monks to hold firm, thoroughly reject the excesses of the acquisition of personal wealth and ease. But the community does have a treasury of the greatest wealth to honor with all the honors which can be given in this world, and this wealth is the Dhamma which they are bound to preserve and protect so that all can find refuge in the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha.

The Buddha teaches us that aside from walking the path to liberation for yourself, the best thing one can do is to support the Sangha in its mission to preserve and protect the Dhamma, ensuring that all beings will continue to be able to find the path to the final enlightenment which the Buddha explained so eloquently. By upholding the Sangha which holds fast to the Dhamma, we pass on to those who come after us a compass which points us unerringly in the right direction on the path to liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth.

The ornate temples and meditation rooms in the monasteries, standing in stark contrast to the simple garb, self-denial, and poverty of the monks, point the seekers after liberation towards the path the Buddha showed us. They show us that the path to liberation is worth every worldly honor, that its cost is like that of building the finest temples, and that those who walk the path must give up the pursuit of wealth and pleasure to reach its end.

In the end, the Sangha is the repository of the Dhamma of the Buddha which he left in the world for us; the Sangha is the Buddha's boat, the ship of the Sakyan son in which we can take refuge as we cross to the other shore surely by following always the light of the Buddha himself, he who is the lighthouse.

By Unknown - http://www2.odl.ox.ac.uk/gsdl/cgi-bin/library?e=d-000-00---0orient01--00-0-0-0prompt-10---4------0-1l--1-en-50---20-about---00001-001-1-1isoZz-8859Zz-1-0&a=d&cl=CL1&d=orient001-aaf.14, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41190754

Note: For those who are interested, you can find more information about the anthology I'm using on my Sources page.

Tuesday, March 15, 2016

Fair Questions: Why use the Pāli Canon to understand Buddhism?

Those who have been reading my many pieces on Buddhism (ranging from lengthy expositions on karma, enlightenment, and morality to explorations of its intersection with contemporary political movements such as socialism and feminism to questions of comparative religion related to Christianity and atheism) may have noticed that my constant source is the Buddha's discourses as they are recorded in the Pāli Canon. And those who are aware that it is not the only source for the discourses of the Buddha might wonder why I choose to use it over other options.

So why do I use the Pāli Canon almost exclusively when trying to understand Buddhism? For many of the same reasons that others do, as it turns out. It is the earliest record we have of the Buddha's discourses in writing and staggeringly comprehensive. Judging by the length of the canonical texts as a whole (which far outstrips even the longest canon of the texts of the Bible), the Buddha would have had to have lived for quite a long time and done quite a lot of public speaking in order for the Buddha and his disciples to produce that many discourses.

It's important to note that the relative age of a text is no guarantee of perfect fidelity to a speaker's message. I have no illusions about that. I do, however, have a sense that the more removed a text is from the speaker (whether by culture, language, or time) the more likely it is to be even less faithful to the speaker's message. And in fairness, the Pāli Canon wasn't recorded until several hundred years after the Buddha's passing on, which is pretty far removed compared to the Gospels of Christianity that were written decades after Jesus' death.

We might reasonably suspect that the Pāli Canon could well be less faithful to the Buddha's teachings than the canonical Gospels are to Christ's teachings, but I tend to give the Pāli Canon the benefit of the doubt since it's the best textual evidence I have. I also tend to give it the benefit of the doubt because it is remarkably coherent both in style and substance. The kinds of repetition recurring across many discourses, both of phrases and themes, suggests that the content of the message is coming from a single speaker or perhaps a group of people very much trying to remain faithful to the words of a single author.

Many people might find it unbelievable that the oral tradition preserved by monks could ever remain faithful to the Buddha's teachings over the course of 400+ years, but there's actually good scientific evidence that human beings are quite capable of preserving accurate information by oral tradition for many thousands of years and then communicating it effectively in a new language. Which is good for assessments of the authenticity of the Pāli Canon, because it's not exactly written in a language that's widely used by native speakers today.